Introduction1

Readers of the New Testament, both ancient and modern, have long puzzled over the literary relationship between the first three gospels accounts, the Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, and Luke, respectively.2 Traditionally, the Synoptic Problem,3 as it is often called, has been approached through established avenues of Biblical exegesis.4 Methods like textual criticism5 as well as source and redaction criticism6 have yielded insight into the Synoptic Gospels’ history of composition, which has coalesced into a number of theories offering explanations for the texts’ origins. Modern scholarship has divided itself into several camps that claim to have a superior explanation of the Synoptic Gospels’ literary relationship and historical origins. While the number of these camps seems to proliferate with increasingly complicated theories, four camps serve as pillars for synoptic studies,7 these are: The Two-Source Theory,8 the Farrer Theory,9 the Augustinian Hypothesis,10 and the Griesbach Hypothesis.11 A large portion of scholarly debate in synoptic studies centers on the merits of the Two-Source Theory, which supposes Markan priority and a hypothetical document “Q” to account for Matthean and Lukan independence,12 and the Farrer Theory, which supposes Markan priority without “Q” on the basis that Matthew and Luke knew each other.13 The Q non-Q debate has stimulated the use of other methods, such as narrative criticism14 and rhetorical criticism,15 to examine the nuanced compositional arguments made by the gospel authors.16 In addition to the various forms of analysis just mentioned there have also been attempts to employ statistical models and other quantitative analyses to determine Matthean and Lukan independence or dependence.17

However, New Testament scholars have been ambivalent as to how empirical data and statistical analyses of the Synoptic Gospels are meant to function within synoptic studies.18 There is no clear consensus on how data can be used to study the gospel texts and what empirical data can say about them. On the one hand, many New Testament scholars are hesitant to use quantitative data and empirical analyses within synoptic studies. Such scholars are often skeptical of the ability for a quantitative method to aid the qualitative methods of traditional exegesis.19 On the other hand, some synoptic scholars have been overly positivistic about what data and statistics can do when studying the gospel texts. Such scholars sometimes see quantitative approaches as being able to provide definitive solutions to the Synoptic Problem while others see it as a means to supplement the veracity of gospel source theories already in existence.20

However, these two extremes are misplaced. It is my intention to show that empirical data collected from the Synoptic Gospels and the responsible analysis of this data can aid exegetes in examining the texts and open up new avenues of interpretation. I argue that empirical analysis of the synoptic texts can be used on a micro-scale, that is, empirical data can aid in the direct interpretation of individual pericopae. In this regard I hope to move the utility of data from the Gospels beyond the confines of its current position in synoptic studies, viz., its application to the Synoptic Problem. To do this I highlight two functions data has regarding the interpretation of texts.

(1) Data collected from empirical analysis of the Synoptic Gospels can be used to visualize the texts. This is a point that is often overlooked by scholars who both do and do not employ statistics in their works. While some studies, such as those of Morgenthaler and Abakuks, visually represent levels of agreement among the texts they do so in order to display overall trends throughout entire gospels.21 However, in order to benefit the exegesis of individual pericopae the most the data needs to be displayed in a way that highlights the details of the texts themselves, not just overall trends. Here data and the digital humanities come into conversation with one another. A digital representation of the Synoptic Gospels amalgamates a textual interface of the Gospels with the quantified data behind each point of the text. In other words, a digital synopsis allows scholars to read the texts in the conventional sense, that is word by word, while at the same time being cognizant of broader trends behind the texts regarding quantifiable data.22 I thus argue that collecting and analyzing data from the Synoptic Gospels need not be confined to proposing a solution to the Synoptic Problem but is in fact a step in the process of operationalizing exegesis through the digital humanities.23

(2) Data can be used to aid the interpretation of texts. Here I argue for an interpretation of a pericope based on a feature of the text uncovered by my empirical analysis and digital synopsis. Specifically, I argue that Matthew and Luke preserve a saying attributed to Jesus found in their common source Mark about the authority of the Son of Man to forgive sins in the Healing of the Paralytic and both alter slightly the grammatical presentation of forgiveness elsewhere in the pericope as a means to fulfill the expectations of Jesus’ messianic identify as set up in each of their respective introductions. One the one hand, Matthew’s emphasis rests on Jesus’ present forgiveness among human beings as a fulfillment of his messianic title, Emmanuel; Luke, on the other hand, situates forgiveness as a past promise that is subsequently fulfilled in the presence of Jesus’ ministry of forgiveness and release.

Synoptic Scholarship and the Empirical Approach

Data as a Solution to the Synoptic Problem

In order to support either the Two-Source Theory or the Farrer Theory some scholars have turned to modeling the Synoptic Gospels using statistics.24 While these scholars have taken many differing approaches in their works there remains one commonality between them namely, they all address a solution to the Synoptic Problem as a whole. Most often, empirical data from the Gospels is used to posit a literary relationship, or lack thereof, between two or more synoptic texts. In this way the data is used to provide a wholistic solution to the Synoptic Problem. In doing so these studies have taken an overarching approach that marginalizes the qualitative assessment of Biblical exegesis in favor of a positivistic commitment to data. The goals, as stated by some of these studies, is indicative of this commitment. For example, A. M. Honoré uses a statistical approach to study the validity of Markan priority. In his assessment, the basis for postulating Markan priority needs a better foundation that is less susceptible to the whims of scholarly intuition. He writes:

Surely the modern critical opinion should either be put on a firm statistical foundation or abandoned? It was with this in mind that I undertook the present study. I hope that, quite apart from the results, the methods may be of some interest. Since they are statistical, they can at best lead to results which can claim a high degree of probability. On the other hand they are or should be more firmly based than mere intuition.25

While this statement should not be taken to mean that Honoré believes statistics are superior to the work of Biblical scholars, he does see his approach as being able to provide a more reliable assessment of the relationship between the synoptics when it comes to Markan priority. Honoré ends his study with definitive statements on the validity of Markan priority, Matthew’s and Luke’s use of Mark as a source, and Matthean and Lukan independence of one another through the existence of other sources, though he does not postulate the exact features of these sources.26 In this regard, Honoré focuses on how the synoptic texts relate with one another and gears his conversation towards a solution to the Synoptic Problem premised on a positivistic commitment to empirical data.

The preoccupation with a solution to the Synoptic Problem is present in other scholarly works that seek to quantify the synoptics. Some of the more extensive collections of statistical data on the synoptic texts are found in the works of Robert Morgenthaler, and Joseph Tyson and Thomas Longstaff. 27 The goal of Tyson and Longstaff is to create a tool that can benefit scholars in arguing for or against various solutions to the Synoptic Problem. While they do not align themselves with a particular source theory, they remain committed to examining overarching solutions to the Synoptic Problem through the use of empirical analysis. They write in their preface:

The purpose of the Synoptic Abstract is to present an analysis of the verbal agreements among the Synoptic Gospels and to do so without a presupposition about the correct solution to the Synoptic problem. We have operated under the conviction that scholars now need a neutral tool which can be used in the comparison of one gospel with another, a tool which treats verbal agreements as important phenomena which can be studied without dependence on a solution to the source problem.28

Here, “dependence” to a solution for the sources means a presupposition about the validity of a source theory for the synoptics. Tyson and Longstaff thus see their work as a means to buttress solutions to the Synoptic Problem and not necessarily as a means to provide insight to the interpretation of the texts. Likewise, Morgenthaler positions his statistical study of the synoptic texts in relation to solving the Synoptic Problem. After a survey of scholarly literature on the use of synopses, Morgenthaler states two observations about the nature of synopses that characterize his approach: (1) “The Synoptic Problem is based on quantitative facts,” and (2) “These quantitative facts can be graphically represented.”29 He then goes on to state that these two observations dictate how any solution to the Synoptic Problem is to be conceived, writing, “As a result, a solution to the Synoptic Problem will only be possible on the basis of a description and recording of the quantitative facts and a clear – synoptic – representation of the relevant results.”30 In this sense, Morgenthaler positions his work as a means to demonstrate a solution to the Synoptic Problem itself and not to interpret the texts individually. However, he does point toward one useful feature of quantitative approaches when it comes to synoptic studies namely, the ability to visualize the texts in various ways.

Other statistical studies of the Synoptic Gospels, while abandoning the supposition that statistics alone can offer an impartial solution to the Synoptic Problem, have maintained a commitment to using empirical data to study to overall relationship between the gospel texts. Andris Abakuks, a professional statistician interested in the Synoptic Problem, has examined the usefulness and limitations of statistical analysis regarding the Synoptic Gospels in great detail.31 Abakuks uses a statistical model to look for places in entire synoptic texts where there is a possible association between Matthew and Luke. Yet unlike other statistical studies, Abakuks moves from a macroscopic analysis of the texts to an examination of those individual pericopes which his statistical method identified as important to Matthean and Lukan dependence of one another. Thus, in light of his broader statistical model, Abakuks begins to engage in more direct exegesis of certain passages in order to see how the conclusions put forward by, “the statistical models, with their simplifying assumptions, turn out to be when faced with the complexities of the texts themselves.”32 Abakuks is thus forthcoming about what statistics and empirical analysis can achieve in synoptic studies, viz., they cannot be a definitive solution to the Synoptic Problem but can point to certain patterns that may aid the scholarly study of the texts. Abakuks’s approach thus acknowledges the need to pair the quantitative and qualitative methods of synoptic study in such a way as to allow them to complement one another and thereby leverage new insight from the texts. In this regard, Abakuks’s work is an effort to use statistics in a way that moves beyond offering a solution to the Synoptic Problem. However, Abakuks’s approach still falls short in this regard because his analysis of the individual pericopae is always geared toward finding a literary relationship between the texts. His conclusions about the individual pericopes he examines hope to provide insight into a possible literary relationship between the synoptics, emphasizing the implications of the analysis for the Two-Source Theory and Farrer Hypothesis.33 Thus, Abakuks’s approach moves towards a meaningful engagement between quantitative and qualitative modes of analysis, but ultimately maintains the connection between a wholistic understanding of the Synoptic Problem and empirical analysis of the synoptic texts.

In sum, empirical analysis in synoptic studies has largely been relegated to studying the Synoptic Problem and, in particular, to interacting with source theory solutions to the Synoptic Problem.

Skepticism Towards Data in Synoptic Studies

When New Testament Scholars do use quantitative methods to analyze the Synoptic Gospels they are often met with criticism. One of the more major criticisms, which represents a major challenge to both quantitative and qualitative methods alike, has do with the ways textual agreements are counted and tabulated within such studies.34 There are several types of textual agreements within synoptic studies, usually having to do with agreements between Matthew and Luke against Mark: the so-called “minor-agreements.”35 Frans Neirynck’s work on the minor-agreements demonstrates the complex interpretive issues of defining an agreement in the synoptics and the level of variability that exists in how scholars come to identify a feature of the texts as an agreement, a level of variability that has only increased since his work was published in 1974. 36 Thus, another goal for scholars, such as Tyson and Longstaff, is to supply a catalog of textual agreements that displays them in a neutral setting without preference for one source theory over another.37 But in any case, it can be said that synoptic scholars seldom agree on agreements.

Depending on the approach of a particular statistical study and how agreements between the texts are measured some scholars support the Two-Source Theory,38 some support the Farrer Hypothesis,39 some support a mixture of approaches.40 This has led to a scholarly critique against the overall use of statistical methods and empirical data when addressing the Synoptic Problem.41 John Poirier, for example, writes, “Rather than lifting the study of the gospels from the mire of subjective judgment, or allowing us to get a handle on a unwieldy mass of data, statistical studies have too often amounted to coded expressions of their user’s commitments.”42 In this regard, empirical studies of the synoptic texts contain the same subjective criteria and exhibit the same types of interpretive issues that are already present in existing methods of Gospel scholarship. Other scholars have been similarly despondent of the ways in which data analysis in the synoptics can aid our understanding of the texts. E. P. Sanders and Margaret Davies, for example, do not see statistics as a definitive means of determining a possible relationship between Matthew and Luke due to the minor agreements, they write: “Statistics seem not quite to settle the question. One is not dealing with random probability, but with editorial choice.”43 However, Sanders and Davies rightly do not dismiss the usefulness of an empirical analysis of the minor agreement outright; they see the high number of agreements between Matthew and Luke, over one-thousand in their assessment, as “too many to attribute to coincidence and editorial policy.”44 Thus, they affirm that an empirical catalog of the synoptic texts can yield insight, but is not meant to be a wholistic explanation of the texts’ literary relationship.

The criticisms of quantitative data in synoptic analysis is thus linked to previous studies which used Gospel data primarily to focus on offering a maximal solution to the Synoptic Problem. A wholistic skepticism of empirical methods in synoptic studies has thus arisen because it is reacting against the wholistic view that data collected through statistics and empirical analysis are able to explain entirely the nuanced nature of literary composition.45 In other words, the quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis have excluded one another. There is thus a need to demonstrate how a quantitative approach to examining the Synoptic Gospels can aid the qualitive methods of traditional Biblical exegesis.

The remainder of this paper covers three topics that seek to illustrate the contribution quantitative analyses can make towards synoptic exegesis. First, I examine the use of a particular form of empirical analysis, viz., contingency tables as used by Abakuks, as a possible and accessible means for exegetes to make source critical judgments about a pericope. Alongside contingency tables, I summarize how the quantitative features of the texts can be visualized and catalogued through a digital medium, which draws attention to important features of the text for the purposes of interpretation. Lastly, I proceed to interpret the pericope of the Healing of the Paralytic by using a contingency table generated from the digital visualization/catalogue of the pericope as a guide to my exegesis.

An Empirical Analysis Approach: Contingency Tables46

In his study of the Synoptic Gospels, Abakuks makes use of contingency tables to look for possible associations between Matthew and Luke.47 I have chosen to adopt this method of analysis in this paper and wish to state clearly here what my intentions are for doing so. First, a contingency table is by no means the only or best method of analysis as regards the Synoptic Gospels, but it is perhaps the simplest method that can be used by Biblical exegetes who likely do not have expertise in more advanced statistical modeling. The simplicity of the contingency table allows me to show how empirical analysis can aid exegesis in a way that most Biblical scholars can understand without too much additional effort.

Second, a contingency table is not meant to make a definitive statement about the literary relationship of one gospel author with another. In fact, a contingency table used in the setting of synoptic scholarship is meant to avoid the pitfall of making the statistics determinative of the texts’ relationship. Because the synoptics texts are not random samples, the data put into a contingency table from the texts cannot determine statistical significance.48 This is to say that a contingency table can point an exegete in the direction of a possible literary connection between two texts, but it must be left to the exegete to make an argument for why such a relationship is warranted. Such an approach thus allows both the quantitative and qualitative methods of analysis to work side by side.

Third, a contingency table is meant to be flexible in that it can be used to test various literary relationships so long as the data is arranged accordingly. In this paper, for example, I arrange the data to look for possible associations between Matthew and Luke. Thus, my approach is working from the basis of Markan priority. There is, of course, no complete agreement on the matter of Markan priority, but I find the evidence in favor of Mark being the earlier source from which Matthew and Luke gathered much of their material to be the most convincing.49 However, one does not have to accept Markan priority to see the value of a contingency table, it could easily be used to test for connections between other gospels texts and other source hypotheses. Additionally, in this paper I have chosen to focus on word agreements between the texts and not strings of agreement, i.e. where the texts agree in how words are arranged syntactically. I do this because looking at the morphology of words in synoptic pericopes gives a larger data set than strings of words. However, one could still use a contingency table to examine relationships between strings of words based on the same principles as word counts.

With these principles in mind, what follows is a brief explanation of how a contingency table works in this approach and how one is able to complete the table for a given pericope.

Table 1: Contingency for Synoptic Analysis

|

|

|

Gospel Y |

|

|

|

|

|

0 (omit) |

1 (include) |

Total |

|

Gospel X |

0 (omit)

|

Unique Z (expected Z)

|

B (expected B)

|

Z + B

|

|

1 (include) |

A (expected A) |

T (expected T) |

A + T |

|

|

|

Total |

Z + A |

B + T |

Total Words Gospel Z |

The table is arranged to test whether Gospels X and Y have a possible association with one another based on their redaction of Gospel Z. The center cell is filled in with the observed data from each gospel. The count of words unique to Gospel Z is placed in the top left corner because both Gospel X and Gospel Y omit these words from their texts. The count of words included in Gospel X and Gospel Z but omitted from Gospel Y is placed in the bottom left corner, labeled A. The count of words included in Gospel Y and Gospel Z but omitted from Gospel X is placed in the top right corner, labeled B. The count of words which appear in all three gospels is placed in the bottom right corner, labeled T. The sums of the observed data are placed in the Total row and column of the table. Finally, the total word count of Gospel Z is placed in the outside bottom right corner; this total will be the same as the sum of the Total row or Total column.

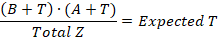

Once the observed data has been placed in the table, the expected value of word counts can be calculated and placed in the parentheses of the table. To calculate the expected frequency, you multiply the sums of the totals rows for a given contingency, i.e. for words that are omitted or included, and divide that product by the total number of words in Gospel Z.50 For example, the expected frequency of words found in all three gospels (T) is calculated:

To see whether there is a possible association between Gospel X and Gospel Y you compare the diagonals of the table. The first diagonal compares the upper left corner of the middle cell with the lower right corner of the middle cell: Unique Z with T. The off diagonal compares the lower left corner of the middle cell with the upper right corner of the middle cell: A with B. If the observed frequencies of the first diagonal are larger than the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies of the off diagonal are smaller than the expected frequencies, then there is a positive association between Gospels X and Y. To put the matter in source critical language, a positive association means that Gospels X and Y likely knew one another in their composition.

Here I give a brief summary of three contingency tables outlining a variety of synoptic pericopae. My intention here is not to make an exhaustive survey of the Synoptic Gospels, but to demonstrate the various features and questions a contingency table can uncover for studying the texts. Each table contains my own counts for verbal agreements among the texts. Inevitably, these counts will vary depending on how one defines an agreement. This, however, is quite useful when examining the texts as it allows scholars to make comparisons of the texts based on different levels of stringency.

The Beelzebul Controversy (Mt 12:22–30; Mk 3:22–27; Lk 11:14–23)51

The Beelzebul Controversy appears in all three synoptic gospels, as well as the document Q. The telling of this episode differs drastically among all three synoptics. However, there are three main features of the pericope that all three gospel writers maintain. The first is an accusation brought against Jesus that he casts out demons by the ruler of demons, Beelzebul (ἐν Βεελζεβοὺλ τῷ ἄρχοντι τῶν δαιμονίων ἐκβάλλει τὰ δαιμόνια [Lk 11:15; cf. Mt 12:24; Mk 3:22]).52 The second is Jesus’ response, which has to do with the ability of a kingdom divided against itself to stand (Mt 12:25–26; Mk 3:24–26; Lk 11:17–18). The third is another statement by Jesus on the ability to plunder a strong person’s house (Mt 12:29; Mk 3:27; Lk 11:21–22). Yet, even these three features are not consistently represented across the texts as there is a great deal of variation in how each author presents them, both syntactically and thematically. For instance, the longest string of material from Mark that appears in all three gospels is only eight words long (ἐν τῷ ἄρχοντι τῶν δαιμονίων ἐκβάλλει τὰ δαιμόνια [Mk 3:22]).53 Even then, the authors arrange this string in different ways so that the longest unbroken chain of material from the three gospels authors is only three words long (ἐκβάλλει τὰ δαιμόνια [Mk 3:22]).54

The observed frequencies of agreement and non-agreement between the synoptic gospels in this pericope, along with the expected frequencies in parentheses, are given in Table 2 in the appendix. The diagonals of the observed data are larger than the expected, while the off diagonals are smaller than the expected, suggesting a positive association between Matthew and Luke. Because the features of the texts differ from one another syntactically so often it is difficult to pinpoint an area of common Matthean and Lukan redaction of Mark in places where all three Synoptic Gospels contain similar material.55 In places where Matthew and Luke agree against Mark, however, the contingency table exhibits a need for further interpretation. For example, Matthew and Luke have a large section in which Jesus discusses the presence of the Kingdom of God vis-à-vis his casting out demons.56 Given the current set up of the contingency table, such an instance may indicate Matthean and Lukan dependence; but the contingency table may also be readapted to test for another possible literary association, namely an association between Matthew, Luke, and Q. The Beelzebul Controversy thus illustrates how a contingency table can serve as a helpful guide to interpretation because of the variation across all three synoptic texts, and as flexible tool that can test multiple possible literary relationships.

The Rich Young Man (Mt 19: 16–30; Mk 10:17–31; Lk 18:18–30)57

“The Rich Young Man/Ruler” appears in all three synoptic accounts. This section of the synoptic texts contains two main features. First is a brief dialogue between Jesus and a certain rich young man (Mt 19:16–21; Mk 10:17–21; Lk 18:18–22). This dialogue involves the young man asking Jesus what he must do to have eternal life. Jesus responds by saying that he should follow the commandments. The young man responds that he has kept the commandments to which Jesus replies that he should then sell his possession and give to the poor. The young man goes away saddened because he had many possessions (Mt 19:22; Mk 10:22; Lk 18:23). This dialogue is followed by the second feature of this section, a saying from Jesus concerning the nature of the kingdom of God/heaven and its eschatological rewards. The saying about the kingdom of God contains two parallel features: first a statement on how it is difficult for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven (Mt 19:23; Mk 10:23; Lk 18:24), second a comparative hyperbole on how it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God (Mt 19:24; Mk 10:25; Lk 18:25). This is followed by an exchange on who is able to be saved, what it possible for God, and an interjection by Peter that those following Jesus have left everything (Mt 19:25–27; Mk 10:26–28; Lk 18:26–28). Finally, the section closes with a promise that those who have left their house and relatives to follow Jesus will receive back these things and more in eternal life (Mt 19:29; Mk 10:29–30; Lk 18:29).

The observed frequencies of agreement and non-agreement between the synoptic gospels in this pericope, along with the expected frequencies in parentheses, are given in Table 3 of the appendix. The diagonals for the observed data are greater than the expected, and the off diagonals are less than the expected frequencies. This indicates a possible positive association between Matthew and Luke and should thus guide our interpretation of the texts. However, because this pericope may be divided into two small subsections, I also present contingencies tables for these smaller sections. Jesus’ interaction with the rich young man displays a positive association between Matthew and Luke, as indicated by the larger observed diagonals, and the smaller observed off diagonals (see Table 4). The contingency for Jesus’ saying about the riches and rewards of discipleship also display a positive association between Matthew and Luke (see Table 5). On the whole, then, we should look for places in these pericopes where Matthew and Luke may be aware of one another. This pericope demonstrates another flexible feature of contingency tables, viz., they can be used to look at expanded or condensed versions of the texts and thereby give important information for even small features of the gospel stories, not just wholistic overviews of entire gospel relationships.

The Sick Healed at Evening (Mt 8:16–17; Mk 1:32–34; Lk 4:40–41)58

Finally, the Sick Healed at Evening shows how a contingency table can open up further discussion on a possible literary connection between Matthew and Luke. Again, this pericope appears in all three Synoptic Gospels and come directly after the Healing of Peter’s Mother-in-Law (Mt 8:14–15; Mk 1:29–31; Lk 4:38–39). The entire scene is brief. Each version of the story contains a statement about the time of day, particularly that is was late in the day, and a description of sick and demon possessed persons being brought to Jesus and Jesus healing them. The observed frequencies of agreement and non-agreement between the synoptic gospels in this pericope, along with the expected frequencies in parentheses, are given in Table 6 of the appendix. The diagonals of the observed counts are smaller than those of the expected frequencies. Additionally, the off diagonals are larger than the expected frequencies. This indicates that there is not a positive association between Matthew and Luke in this pericope. On closer inspection, we can see that the observed and expect frequencies are nearly equal to one another. This means that depending on how one attributes verbal agreement between the texts the contingency table could point in either the direction of Matthean and Lukan dependence or of independence. This example thus serves to demonstrate how a contingency table cannot be taken to be determinative of the texts’ literary relationship but can be used as a guide to postulate a literary hypothesis based on the quantifiable data one chooses that is available from the pericopes. In other words, this pericope requires close qualitative interpretation alongside any quantitative analysis.

Evaluation of Empirical Data and Contingency Tables

The use of contingency tables is meant to demonstrate three aspects about the use of quantifiable data in the study of the Synoptic Gospels. First is simplicity. Each of the previous contingency tables presents their respective pericopes in a concise and easily read diagram. A cursory glance at each table allows an exegete to make quick interpretive judgements on the literary relations between each section of the texts. The contingency tables are thus a simple tool that guides the beginning stages of exegesis.

Next is scholarly interpretation. While the contingency tables provide some initial insights into each pericope’s literary relation among the Synoptic Gospels, the pericopes are still subject to scholarly interpretation. For example, the contingency table for the pericope of the Sick Healed at Evening exhibits neither a robust positive association between Matthew and Luke nor a definitive indication of their literary independence. In such a case the contingency table calls for closer examination of the texts and thus does not close off avenues of interpretation based on a wholescale commitment to quantifiable data.

Last is flexibility. The previous contingency tables were designed to test for possible literary associations between Matthew and Luke on the basis of Markan priority. This was done because of the prevalence of the Two Source Hypothesis and the Farrer Hypothesis, which require such a design. However, a contingency table need not be limited to this set up. For example, a contingency table could be adapted to test for associations between Mark and Luke in order to study their literary relationship. Likewise, the Gospel of John, Gospel of Thomas, or Q could be substituted into a table to test for associations between the sections of these texts and other early Jesus literature. For example, in the Beelzebul Controversy the contingency table could be readapted to test the association between Matthew, Luke, and Q given the large amount of Matthean and Lukan agreement against Mark.59 In short, a contingency table has a variety of uses and does not need to be limited in its use to studying a wholistic relationship between the Synoptic Gospels, it can be adapted to study smaller sections of text and to examine relationships between extra-canonical sources.

An Empirical Exegesis: The Healing of the Paralytic (Mt 9:1–8; Mk 2:1–12; Lk 5: 17–26)60

Having argued against the wholesale dismissal of quantifiable data and statistical analysis from synoptic interpretation, I now offer a brief exegetical essay on the Healing of the Paralytic. My exegesis will be informed by a contingency table that serves as a guide to my literary interpretation. In all, I endeavor to demonstrate the usefulness of such a statistical analysis to exegeting the Synoptic Gospels.

Overview

“The Healing of the Paralytic” occurs in all three Synoptic Gospels. Mark and Luke place the pericope is the same relative order within their accounts, while Matthew slightly alters its position.61 In all three synoptics the Healing of the Paralytic is followed by the Call of Levi/Matthew (Mk 2:13–17; Mt 9:9–13; Lk 5:27–32) and then by the Question about Fasting (Mk 2:18–22; cf. Mt 9:14–17; Lk 5:33–39). While each telling of the story differs from the others in various ways there are several components that are present in each. All three synoptics describe a paralytic being brought to Jesus. Jesus recognizes the faith of those who brought the man to him and says to the paralytic, ἀφίενταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι (Your sins are forgiven [Mt 9:2; Mk 2:5; cf. Lk 5:20]).62 This initiates a discussion among the bystanders, either scribes or scribes and Pharisees, involving an accusation that what Jesus has said is blasphemy/blasphemous. Jesus, however, realizes what is being discussed and responds with a question. He asks the bystanders whether it is easier to say, ἀφίενταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι (Your sins are forgiven), or to say, ἔγειρε καὶ περιπάτει (Get up and walk [Mt 9:5; Lk 5:23; cf. Mk 2:9]).63 Then without allowing a chance for his audience to respond, Jesus makes a statement by which the onlookers can confirm or deny his ability to forgive sins; he says, ἵνα δὲ εἰδῆτε ὅτι ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας (But in order that you may know that the son of man has authority on the earth to forgive sins… [Mk 2:10; cf. Mt 9:6; Lk 9:24]).64 Jesus then tells the paralytic to get up and go home.65 The paralytic does so, and the crowd reacts to the miracle with amazement and/or awe.

Empirical Analysis

The observed frequencies of agreement and non-agreement between the Synoptic Gospels in the Healing of the Paralytic, with the expected frequencies in parentheses, are given in the following table.

Table 7: Contingency for the Healing of the Paralytic (Mt 9:1–8; Mk 2:1–12; Lk 5:17–26) (Form/Lemma)

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

96 / 75 (71.54 / 50.40)

|

27 / 36 (51.46 / 60.60)

|

123 / 111

|

|

1 |

18 / 14 (42.46 / 38.60) |

55 / 71 (30.54 / 46.40) |

73 / 85 |

|

|

|

Total |

114 / 89 |

82 / 107 |

196 |

Looking at the diagonals, we can see that the observed frequencies of words which Matthew and Luke simultaneously omit or retain from Mark are greater than the expected frequency had Matthew and Luke be statistically independent of one another. Likewise, we can see that the off diagonals are less than the expected frequency for changes that occur only among Matthew or only among Luke. This suggests a positive association between Matthew and Luke based on their redaction of Mark and should inform our interpretation of the texts.

Given this information, however, it is interesting to note that the visualization of the texts does not reveal a high degree of agreement between Matthew and Luke.66 There are only 9 words that constitute a minor-agreement in both lemma and form between Matthew and Luke, which translates to only 7% of the words in the Matthean version and 4% in the Lukan version being minor-agreements.67 The largest agreement is only 5 words long: ἀπῆλθεν εἰς τὸν οἶκον αὐτοῦ (he returned to his home [Mt 9:7; Lk 5:25]). At first, it would seem that Matthew and Luke include this phrase to make the story consistent with Jesus’ prior command: ὕπαγε/πορεύου εἰς τὸν οἰκόν σου (Get up/go to your home [Mt 9:6; Lk 5:24; cf. Mk 2:11]). However, Matthew and Luke are not consistent in maintaining a similar type of cohesion throughout the text. For example, while both Matthew and Luke omit the phrase καὶ ἆρον τὸν κράβαττόν σου (and take up your mat) found in Mark 2:9 (cf. 2:11), which deals with what would be easier to say to the paralytic, Luke, for his part, retains the action of the paralytic taking up the thing on which he laid (ἄρας ἐφʼ ὅ κατέκειτο [Lk 5:25]) but Matthew does not. There is thus an inconsistency in how Matthew and Luke seem to redact Mark; Luke sometimes omits things from Mark that Matthew also omits, but at the same time Luke retains material from Mark that Matthew omits. This observation and the tally of agreements alone would perhaps be enough to justify the conclusion that such agreement between Matthew and Luke is coincidental.68 However, as the contingency table has already indicated there is a possible positive association between Matthew and Luke based on their common redaction of Mark without recourse to the minor-agreements. The use of a contingency table thus allows us to justify a reading of the text where Matthew and Luke are in conversation with one another even though the appearance of agreement between Matthew and Luke is relatively low. In other words, the contingency table provides an analysis of the observable data that would otherwise have been dismissed as coincidental.

Because we can postulate a literary connection between Matthew and Luke in this pericope apart from the minor-agreements we can set them aside for the time being and turn our attention to another feature of the texts where Matthew and Luke seem to be in conversation with one another, namely words that appear in all three synoptic accounts. The visualization of the texts reveals two points that exhibit a high degree of shared material among all three authors. The first is Jesus’ reception of those carrying the paralytic and his statement to the paralytic himself. Each gospel author records to some degree, καὶ ἰδὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς τὴν πίστιν αὐτῶν (and when Jesus saw their faith [Mt 9:2; Mk 2:5; cf. Lk 5:20])69 followed by Jesus telling the paralytic ἀφίενταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι (your sins are forgiven [Mt 9:2; Mk 2:5; cf. Lk 5:20]).70 The second point is Jesus’ question about what is easier to say to the paralytic and his statement on how he will demonstrate his authority to forgive sins (Mt 9:5–6; Mk 2:9–10; Lk 5:23–24). In both these instances the key subjects at hand are forgiveness and sins, as well as the Son of Man.

Given the positive association between Matthew and Luke based on the contingency table and the observation of two textual features on the forgiveness of sins derived from visualizing the texts a question opens up: what might cause Matthew and Luke to persevere a statement from Jesus found in Mark about the forgiveness of sins with such a high level of shared material?

Interpretation

To examine this question, I follow three steps. First, I consider the roll of “sins” in Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts. Next, I move on to consider the motif of forgiveness as it appears in Matthew and Luke. Finally, I bring Matthew’s and Luke’s statements about “sins” and “forgiveness” together in light of their larger literary agendas for designating Jesus as the fulfilment for the prophetic role of God’s Messiah.

Matthew and Luke both feature “sin” and “sinners” as motifs within their narratives.71 However, these motifs are far more frequent within Luke’s account than Matthew’s.72 The largest concentration of sin and sinners in Matthew appears in the Healing of the Paralytic and the subsequent Call of Matthew (Mt 9:1–13; cf. Mk 2:1–17; Lk 5:17–32). Addionally, the Healing of the Paralytic is the only instance outside of the Last Supper in Matthew (26:28) where Jesus actively involves himself in forgiving sins.73 It is interesting to note that Matthew does not engage with sin frequently given that he introduces the motif as a programmatic confirmation of Jesus’ messianic identity in the birth narrative (1:18–25).74 Specifically, the angel that appears to Joseph tells him to name the child Jesus, αὐτὸς γὰρ σώσει τὸν λαὸν αὐτοῦ ἀπὸ τῶν ἁμαρτιῶν αὐτῶν (1:21).75 Matthew then sets up his programmatic identity motif for Jesus by pairing the angel’s command to Joseph with a prophetic fulfillment statement about Jesus being Ἐμμανουήλ (Emmanuel), or “God with us” (1:23; cf. Isa 7:14).76 In this manner, Matthew sets up the expectation that Jesus’ interactions with sin are related to his messianic identity as God dwelling among people. Matthew bookends this expectation at the close of his gospel in commissioning the disciples, stating: καὶ ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ μεθ᾽ ὑμῶν εἰμι πάσας τὰς ἡμέρας ἕως τῆς συντελείας τοῦ αἰῶνος (Mt 28:20).77 The bookends in Matthew 1:21–23 and 28:20 frame Matthew’s narrative to point to Jesus’ messianic identity as God being with people.

We also see this programmatic expectation fulfilled in the way Matthew presents the Healing of the Paralytic, specifically in how the crowds respond to Jesus forgiving the sins of the paralytic and restoring his ability to walk. All three synoptics, to some effect, tell how the people who saw the miracle were amazed and glorified God (Mt 9:8; Mk 2:12b; Lk 5:26). Matthew, however, does not record what the people said as do Mark and Luke. Instead, he qualifies the description of God with an attributive statement; he writes, καὶ ἐδόξασαν τὸν θεὸν τὸν δόντα ἐξουσίαν τοιαύτην τοῖς ἀνθρώποις (Mt 9:8).78 Two points of syntax in this statement are worth unpacking. First, the demonstrative pronoun τοιαύτην (this/such) qualifies the object of the attributive participle phrase, ἐξουσίαν (authority). “This authority” is the same authority that Jesus exhibits over the paralytic by healing him and forgiving his sins (Mt 9:6). However, the authority that Jesus exhibits is not separate from himself because he wields it as the Son of Man (ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου).79 In this way, Jesus both wields the authority and is the authority given by God which the crowd marvels at in this pericope.80 Second, the dative τοῖς ἀνθρώποις is an indirect object, which could be rendered “to humans.”81 Because τοῖς ἀνθρώποις is plural and because the object ἐξουσίαν τοιαύτην (this authority) refers to Jesus as the wielder of authority and the authority itself, the indirect object in this case cannot be Jesus.82 The dative plural τοῖς ἀνθρώποις thus refers to the communal designation of mankind, or even better, humanity or human beings,83 as the recipients and benefactors of God’s authority, though humanity itself does not wield this authority itself per se.84 The entire phase can thus be translated, “And they glorified God who had given such authority to humans.” The statement τοῖς ἀνθρώποις (to humans) evokes Matthew’s earlier messianic fulfilment text from Isaiah 7:14 (cf. Mt 1:21–23), God sent his Messiah to human beings as Emmanuel (God with us) and he saves people from their sins. Matthew’s version of the Healing of the Paralytic, therefore, serves as a confirmation of Jesus’ messianic identity namely, as God’s Messiah who dwells among human beings and forgives sins.85

Luke engages with sin and sinners far more often in his narrative than Matthew. In addition to the occurrence of “sins” in the Healing of the Paralytic, Luke includes several pericopae in his account where sins and sinners play a prominent role: The Woman with the Ointment (Lk 7:36–50; cf. Mt 26:6–13; Mk 14:3–9), the parables of the Lost and Found (Lk 15:1–32), and the story of Zacchaeus (Lk 19:1–10). Like Matthew, Luke’s emphasis on sins should be expected given that he introduces it as programmatic motif in the opening sections of his gospel account (e.g. 1:77) and Jesus’ sermon at Nazareth (4:14–30), which are later bookended by a commission to proclaim forgiveness of sins to all nations at the close of the account (24:47). These programmatic statements in Luke also include the forgiveness of sins or the release of captives.86 In particular, the sermon at Nazareth serves as a summary statement for Jesus’ later ministry that will bring good news to the poor and release to captives (4:18).87 Like Matthew, Luke includes a prophetic fulfilment statement from Isaiah (61:1–2) about Jesus’ program but has Jesus himself proclaim its fulfilment: σήμερον πεπλήρωται ἡ γραφὴ αὕτη ἐν τοῖς ὠσὶν ὑμῶν (Lk 4:21).88 Jesus’ many interactions with “sin” in Luke thus serve to confirm the expectation of Jesus procuring release for captives through the forgiveness of sins. We can see this Lukan emphasis in Luke’s account of the Healing of the Paralytic, specifically, like Matthew, in how Luke closes out the episode. In additional to describing the witnesses of the miracle being seized with amazement and glorifying God, Luke has them say, εἴδομεν παράδοξα σήμερον (Lk 5:26).89 The word σήμερον (today) here evokes Jesus’ prior statement about his reading of Isaiah in the Nazareth synagogue as being fulfilled σήμερον (today) (Lk 5:26; cf. 4:21). The word σήμερον plays a vital role in proclaiming the presence of Jesus’ messianic fulfilment within Luke’s gospel; it appears in Luke’s nativity scene (2:11), the sermon at Nazareth (4:21), the Healing of the Paralytic (5:26), the episode with Zacchaeus (19:5, 9), and Jesus’ statement to the thief on the cross (23:43).90 By using σήμερον in this pericope, Luke thus sees Jesus’ act of healing the paralytic and forgiving his sins as a confirmation and attribution of his messianic role as one who forgives sins through the release of captives, in this case that of paralysis.

It is evident then, that sins and forgiveness have a role to play in both Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts given their introductory material. While the amount of material about sins differs drastically between Matthew and Luke their use of “sin” in the Healing of the Paralytic serves remarkably similar goals. In Matthew, Jesus’ interaction with “sin” in the Healing of the Paralytic serves as confirmation of his Messianic identity in conjunction with the prophetic fulfillment statement in Isaiah 7:14, namely that Jesus is Emmanuel or God among human beings. Likewise, the Healing of the Paralytic in Luke serves as a confirmation of Jesus’ messianic program of forgiveness and release as a fulfilment of Isaiah 61:1–2 enacted presently, that is, today (σήμερον). Both Matthew and Luke therefore use the Healing of the Paralytic as a confirmation of their programmatic messianic fulfilment passages in relation to their respective prophetic statements from Isaiah. Matthew’s and Luke’s parallel engagement with “sin” in this pericope thus confirms a possible association between the two gospel accounts as suggested by the analysis of the contingency table.

Because of Matthew’s limited references to “sin” in comparison with Luke, the Healing of the Paralytic is the largest point of contact between Matthew and Luke where we can leverage an assertion about how the two authors also emphasize “forgiveness” in relation to one another. Here I take a closer look at “forgiveness” as it appears in Matthew and Luke to see how it operates within the Healing of the Paralytic. The noun ἄφεσις (forgiveness) occurs infrequently in both Matthew and Luke; in Matthew it appears only in the context of the Last Supper (26:28), while in Luke it appears in the programmatic statements about forgiveness at the opening and close of the gospel account (1:77; 3:3; 4:18; 24:47).91 The verbal form ἀφίημι (forgive) is far more frequent in Matthew and Luke. While ἀφίημι can be used in a variety of ways, in Matthew its use designating an act of forgiveness is commonly associated with ἁμαρτία (sin).92 Likewise, Luke commonly uses the term alongside ἁμαρτία (e.g. Lk 5:17–26; 7:47–49; 12:10).93 Thus we can say that “forgiveness” as a motif in Matthew and Luke is closely associated with “sin.”94

“Forgiveness” in the Healing of the Paralytic appears in slightly different fashions between Matthew and Luke. Luke, in particular, renders ἄφιημι in the perfect (ἀφέωνταί, they have been forgiven [5:20, 23]) while Matthew, following Mark, renders it in the present (ἀφίενταί, they are forgiven [Mt 9:2, 5; cf. Mk 25, 9]). There are many possible reasons for this difference,95 but I would like to postulate that the different renderings are the result of Matthew’s and Luke’s opening programmatic statements, which seek to confirm Jesus’ messianic identity in similar yet altered ways. As stated previously, Matthew’s program for Jesus as Messiah is informed by the expectation that God dwells among human beings and forgives sins (Mt 1:21–23). As already argued, Matthew’s inclusion of a qualified description of God who has given authority τοῖς ἀνθρώποις (to humans) at the end of the Healing of the Paralytic is an indication of how he adapts his material to solidify the distinction of Jesus as Emanuel, God among humans (Mt 9:8). The present tense of ἀφίημι in the Matthean version of the Healing of the Paralytic also aids Matthew’s literary agenda in this regard. Specifically, the continuous aspect of the present tense verb draws attention to the presence of forgiveness among the onlookers and directed at the paralytic. In other words, the present tense ἀφίενταί highlights Jesus’ present actions within the story as an indication of his messianic identity connected to his presence among human beings: he is presently among them and heals and forgives sins.96 Matthew’s retention of the present tense from Mark is thus in keeping with his larger thematic goals.

Luke’s program for Jesus, as stated earlier, is informed by the past promise of release for captives found in Isaiah 61:1–2 and its fulfillment at a specific time, today (σήμερον) (Lk 4:18–19, 21). It is fitting, therefore, that Luke in the Healing of the Paralytic renders ἀφίημι in the perfect in order to reflect the completed state of a past action. The paralytic’s sins “have been forgiven” (ἀφέωνταί) because Jesus, in Luke, has already fulfilled (πεπλήρωκεν) the scripture promising release (ἄφεσις) to captives (Lk 4:18–21).97 Luke uses the perfect of ἀφίημι in a similar manner in the pericope about a woman anointing Jesus with ointment (Lk 7:36–50).98 After Jesus has demonstrated to Simon the Pharisee that the woman who came to him fulfilled the role of a host and loved Jesus more than he did,99 he states:

οὗ χάριν λέγω σοι, ἀφέωνται αἱ ἁμαρτίαι αὐτῆς αἱ πολλαί, ὅτι ἠγάπησεν πολύ· ᾧ δὲ ὀλίγον ἀφίεται, ὀλίγον ἀγαπᾷ. εἶπεν δὲ αὐτῇ· ἀφέωνταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι (Lk 7:47–48).100

In this case, the woman’s actions are the result of a previous act of forgiveness. She displays her acts of love because her many sins have been forgiven; by contrast, Simon shows little love because he has only been forgiven little.101 It is interesting to note that in Luke we are not explicitly shown the point at which the woman is forgiven, all we know is that is has already happened at this point in the account. However, when read in light of Luke’s programmatic statement for Jesus’ ministry in his sermon at Nazareth we can see that Jesus’ proclamation of release (ἄφεσις) serves as the past action enabling the completed state of the woman’s acts of love. Therefore, Luke renders ἀφίημι in the perfect in 7:47–48 because he is describing a completed action, which Jesus himself has already fulfilled, that manifests itself though the love of the woman. These two examples, the Healing of the Paralytic and the Woman with the Ointment, demonstrate how Luke articulates Jesus’ ministry of forgiveness vis-à-vis his programmatic goals set forward in the sermon at Nazareth.102

Finally, when we examine Mark’s account of the Healing of the Paralytic, we do not see as clear a development of his programmatic agenda as we do in Matthew in Luke. Mark’s program, instead, can explain the development of Matthew’s and Luke’s agendas for Jesus’ identity and ministry. This indicates a common redaction of Mark by Matthew and Luke that explains their differences in the text. One statement that might be considered programmatic for Mark is Jesus’ preaching in Galilee:103

Μετὰ δὲ τὸ παραδοθῆναι τὸν Ἰωάννην ἦλθεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς εἰς τὴν Γαλιλαίαν κηρύσσων τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ θεοῦ καὶ λέγων ὅτι πεπλήρωται ὁ καιρὸς καὶ ἤγγικεν ἡ βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ· μετανοεῖτε καὶ πιστεύετε ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ (Mk 1:14–15).104

This statement contains two motifs that appear in Matthew’s and Luke’s programmatic agendas. First is the nearness of the Kingdom of God (ἤγγικεν ἡ βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ). In a similar way, we see Matthew pick up on this idea of nearness by rendering the concept of forgiveness in the present tense in order to emphasize the presence of Jesus as Emmanuel and by ending his version of the pericope with an indirect object (τοῖς ἀνθρώποις) to draw attention to the presence of God’s Messiah among human beings. The second motif is fulfilment (πεπλήρωται ὁ καιρὸς). In a similar way we see Luke pick up on this idea of fulfillment by rendering forgiveness (ἀφίημι) in the perfect tense in order to emphasize the completed nature of Jesus’ fulfillment of his messianic identity as one who proclaims release to captives. Matthew and Luke thus articulate their conceptions of forgiveness and the presence of God’s Messiah in the Healing of the Paralytic in ways that parallel one another, which can be attributed to their using Mark as a source of inspiration for their larger programmatic agendas. This serves as an additional confirmation of association between Matthew and Luke based on their redaction of Mark that was already postulated by the contingency table.

I now turn back to the previous assertion that Matthew and Luke preserve Jesus’ statement about the authority of the Son of Man to forgive sins in order to reflect their larger programmatic goals for Jesus’ ministry. As already noted, all three synoptic texts preserve a statement about the Son of Man having authority to forgive sins (Mt 9:6; Mk 2:10; Lk 5:24). We have also noted that the visualization of these texts reveals that each of the synoptic authors preserve this statement with a relatively high degree of agreement between them.105 Addionally, the contingency table for this pericope has suggested a possible association between Matthew and Luke based on their redaction of Mark, which was confirmed by a closer examination of Matthew’s and Luke’s respective presentations of “sin” and “forgiveness.” We should thus anticipate that Matthew and Luke alter their presentations about the Son of Man having authority to forgive sins in parallel manners that are consistent with their respective programmatic agendas.

We can see evidence of Matthew’s alteration of the saying to serve his thematic goals for Jesus’ messianic identity in how he places the prepositional phrase ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς (Mt 9:6).106 Matthew renders this phrase as follows: ἵνα δὲ εἰδῆτε ὅτι ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας.107 We can see that in Matthew’s version the designation Son of Man (ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου) is placed alongside the prepositional phase ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς. By contrast, Mark and Luke group ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς with the complimentary infinitive phrase ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας (Mk 2:10; Lk 5:24).108 While the placement of ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς modifies the infinitive phrase in all three synoptic accounts, Matthew’s placement of it next to the Son of Man helps him emphasize both the location of the Son of Man and the location at which he forgives sins, viz., on the earth. This is in keeping with Matthew’s larger goal of emphasizing that God’s Messiah is among human beings as one who forgives sins. Matthew thus presents this saying in a way that preserves the saying’s integrity, but which also helps him fulfill a programmatic agenda for his gospel account.

There is also evidence of how Matthew and Luke alter this saying to aid their programmatic agendas in how each of them places the infinitive phrase ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας (Mt 9:6; Lk 5:24; cf. Mk 2:10). Luke, like Matthew, places this phrase at the end of the saying: ἵνα δὲ εἰδῆτε ὅτι ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας.109 By contrast, Mark places it before the prepositional ἐπὶ phrase, which ends his version of the saying.110 As previously mentioned, Matthew and Luke introduce the forgiveness of sins as a motif signifying the presence of God’s Messiah and the fulfillment of prophetic expectation of release in each of their respective narratives. On the one hand, Matthew puts forward the expectation that the Messiah is Emmanuel, God dwelling with humans, and will save his people from their sins (Mt 1:21–23; cf. Isa 7:14). On the other, Luke puts forward the expectation that Jesus’ ministry fulfills the prophetic promise of release for captives in the presence of people at a certain time, today (Lk 4:18–21; cf. Isa 61:1–2). In both these programmatic statements, forgiveness, especially forgiveness of sins is emphasized. Likewise, in the Healing of the Paralytic, Matthew and Luke foreground the forgiveness of sins present in Jesus’ earthly ministry and person by placing it at the end of their Greek phrases, thereby signifying its importance for understanding the story in relation to their larger literary goals.

The ways in which Matthew and Luke arrange their statements about the Son of Man having authority to forgive sins thus reflects an association between both texts in this pericope and further confirms the association posited earlier by the contingency table. The association, in this case, which was postulate by the word counts of the text, can be said to be caused by a common redaction of Mark where both authors sought to emphasize their messianic expectations set forward for Jesus in their gospel accounts.

Conclusions on the Use of Empirical Analysis and the Healing of the Paralytic

The use of an empirical analysis to aid the interpretation of the Healing of the Paralytic has been quite useful. Based on the word counts of the synoptic texts alone, a contingency table allowed me to postulate a possible positive association between Matthew and Luke based on their common redaction of Mark. Once this initial observation was made, I then examined a visualization of the texts based on the data from the contingency table. This visualization helped me to hone my interpretation of the texts on a few significant points of agreement shared by all three Synoptic Gospels. I found that all three synoptics preserve a saying about the Son of Man having authority to forgive sins with a relatively high degree of agreement, if not in the order of words at least in the words used. I also found, through the visualization of the texts, that each gospel author preserves a statement about Jesus forgiving the sins of the paralytic man. On further inspection, I noted that Matthew preserves this statement from Mark using the present tense, while Luke alters it by putting it in the perfect. The reason for this has to do with Matthew’s and Luke’s respective programmatic agendas about Jesus’ messianic role. Matthew preserves it in the present to emphasize the presence of God’s Messiah as one who dwells among human beings, Emmanuel. Luke alters it to the perfect to emphasize Jesus’ ministry as the fulfillment of the prophetic promise for release for captives. I found this same type of alteration in how Matthew and Luke each end the pericope: Matthew that such authority, namely Jesus, was given by God to human beings, and Luke that the crowds saw a marvelous thing at the time of fulfilment, viz., today (σήμερον). Finally, the observations made about Matthew’s and Luke’s alterations of this pericope for the sake of their programmatic agendas helped me to explain the subtle differences of the Son of Man statement preserved in the gospel texts. Matthew alters it by arranging the prepositional phrase ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς alongside the designation of Son of Man (ὁ υἱός τοῦ ἀνθρώπου); and both Matthew and Luke place the infinitive phrase ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας at the end of their Son of Man statements to draw attention to their programmatic agendas for the forgiveness of sins.

By using an empirical analysis that employs statistical inference I have thus been able to leverage insight from the texts regarding this pericope. The analysis has not been used to posit a wholistic theory regarding the literary relationship between Matthew and Luke. Rather, the analysis between Matthew and Luke has drawn attention to the parallel ways both texts redact Mark, be it either in words, phrases, or larger literary concerns. In particular, I have found that Matthew and Luke share a larger literary concern for the designation of Jesus as Messiah who fulfills prophetic promises about the forgiveness of sins and who dwells with human beings. The use of data in the study of the Synoptic Gospels has thus shown itself to be useful in interpreting the texts beyond just a solution to the Synoptic Problem.

Conclusion

In this paper I have hoped to demonstrate that statistics in the study of the Synoptic Gospels are neither to be abandoned or relegated to validating sources theories on the Synoptic Problem. Instead, I have argued that empirical analysis of the Synoptic Gospels and the use of statistics to interpret this data remains useful on the level of exegetical interpretation. The adversity quantitative studies of the gospels have met within synoptic scholarship is thus misplaced. Previous studies of the Synoptic Gospels that employed statistics largely did so in order to argue for wholistic literary relationships between the synoptic texts, like those postulated in the Two-Source Theory or Farrer Hypothesis. Biblical scholars thus often met the use of statistics and data in gospel studies with wholistic skepticism because such studies were trying to consolidate entire literary compositions down to numbers, without critical regard for the narrative artistry of the gospel authors. However, when employed on a smaller scale, statistical analysis of the Synoptic Gospels can be of great benefit when interpreting gospel pericopae.

I have demonstrated the utility of a particular method of statistical analysis, that of a contingency table, when it comes to examining individual gospel pericopae in two ways. First, I have shown that a contingency table can be used to examine a variety of texts that differ in size, arrangement, and textual agreements. The flexibility of a contingency table in this regard thus makes it a viable method for examining gospel texts as part of the process of more detailed exegesis. Contingency tables also lend themselves to visualizing the texts in a manner that can aid interpretation. The preliminary database of synoptic pericopae I have constructed is evidence of this type of use and application for data in synoptic studies.111 Finally, I have made an interpretive claim about Matthew’s and Luke’s version of the Healing of the Paralytic using both the empirical method of a contingency table and the digital visualization of the texts. Specifically, I have argued that Matthew and Luke preserve a statement about the Son of Man having authority to forgive sins, as found in Mark, but that both slightly alter the contexts in which this saying appears in order to cohere this statement with their larger respective literary programs for Jesus’ messianic identification within his ministry. On the one hand, Matthew alters his presentation of the statement and its context to emphasize Jesus’ role as Emmanuel, God with human beings, and God’s Messiah who forgives sins. On the other hand, Luke alters his presentation of the statement and its context to emphasize Jesus’ fulfilment of a prophetic promise for the release of captives at a particular time, viz., today (σήμερον). The goals of Matthew and Luke in this regard are parallel to one another in that both seek to present their gospel accounts in ways that cohere with their programmatic expectations for Jesus’ messianic identity. Their respective redactions of Mark, therefore, are parallel, but at the same time are unique to the Matthean and Lukan literary agendas.

Using a statistical approach has helped me to make these interpretive claims. This is thus evidence of the usefulness for engaging in empirical data analysis of the Synoptic Gospels beyond its application to the Synoptic Problem.

Appendix

Table 2: Contingency for the Beelzebul Controversy (Mt 12:22–30; Mk 3:22–27; Lk 11:14–23) (Form/Lemma)112

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

55 / 45 (45.95 / 32.86)

|

2 / 1 (11.05 / 13.14)

|

57 / 46

|

|

1 |

24 / 25 (33.05 / 37.14) |

17 / 27 (7.95 / 14.86) |

41 / 52 |

|

|

|

Total |

79 / 70 |

19 / 28 |

98 |

Table 3: Contingency for The Rich Young Man and On the Riches and Rewards of Discipleship (Mt 19:16–30; Mk 10:17–31; Lk 18:18–30) (Form/Lemma)

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

95 / 78 (75.33 / 52.10)

|

52 / 42 (71.67 / 67.90)

|

147 / 120

|

|

1 |

49 / 44 (68.67 / 69.90) |

85 /117 (65.33 / 91.10) |

134 / 161 |

|

|

|

Total |

144 / 122 |

137 / 159 |

281 |

Table 4: Contingency for The Rich Young Man (Mt 19:16–22; Mk 10:17–22; Lk 18:18–23) (Form/Lemma)

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

29 / 21 (21.09 / 11.55)

|

29 / 20 (36.91 / 29.45)

|

58 /41

|

|

1 |

11 /10 (18.91 / 19.45) |

41 / 59 (33.09 / 49.55) |

52 / 69 |

|

|

|

Total |

40 / 31 |

70 / 79 |

110 |

Table 5: Contingency for On the Riches and Rewards of Discipleship (Mt 19:23–30; Mk 10:23–31; Lk 18:24–30) (Form/Lemma)

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

66 / 57 (54.13 / 42.04)

|

23 / 22 (34.87 / 36.96)

|

89 / 79

|

|

1 |

38 / 34 (49.87 / 48.96) |

44 / 58 (32.13 / 43.04) |

82 / 92 |

|

|

|

Total |

104 / 91 |

67 / 80 |

171 |

Table 6: Contingency for The Sick Healed at Evening (Mt 8:16–17; Mk 1:32–34; Lk 4:40–41) (Form/Lemma)

|

|

|

Luke |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

Total |

|

Matthew |

0

|

24 / 21 (25.11 / 22.17)

|

11 / 13 (9.89 / 11.83)

|

35 / 34

|

|

1 |

9 / 9 (7.89 / 7.83) |

2 / 3 (3.11 / 4.17) |

11 / 12 |

|

|

|

Total |

33 / 30 |

13 / 16 |

46 |

Abbreviations:

| AB | Anchor Bible | |

| BDAG | Bauer, W., F. W. Danker, W. F. Arndt, and F. W. Gingrich. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 3rd ed. Chicago, 1999. | |

| BETL | Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium | |

| BZNW | Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft | |

| CBR | Currents in Biblical Research | |

| HTR | Harvard Theological Review | |

| JBL | Journal of Biblical Literature | |

| JGRChJ | Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism | |

| JSNT | Journal for the Study of the New Testament | |

| JSNTSup | Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series | |

| LCL | Loeb Classical Library | |

| LNTS | Library of New Testament Studies | |

| Neot | Neotestamentica | |

| NIGTC | New International Greek Testament Commentary | |

| NovT | Novum Testamentum | |

| NovTSup | Novum Testamentum Supplements | |

| NPNF1 | Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 1 | |

| NTS | New Testament Studies | |

| PNTC | Pillar New Testament Commentary | |

| ResQ | Restoration Quarterly | |

| SNTSMS | Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series | |

| ST | Studia Theologica | |

| TENTS | Texts and Editions for New Testament Study | |

| WTJ | Westminster Theological Journal | |

| WUNT | Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament |

Bibliography

Primary Sources and Collections:

Aland, Barbara and Kurt Aland, et al., eds. Novum Testamentum Graece. 28th ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2012.

Augustine. De consensus evangelistarum libri quattuor. Sancti Aureli Augustini Opera. Vol. 43. Edited by Franz Weihrich. 1904. Reprint, New York, Johnson, 1963.

Augustine. The Harmony of the Gospels. Translated by S. D. F. Salmond. NPNF1. Vol. 6. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2004.

Eusebius. Ecclesiastical History. Translated by J. E. L. Oulton. Vol. 2. LCL. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932.

Eusebius. Ecclesiastical History. Translated by Kirsopp Lake. Vol. 1. LCL. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1926.

McCarthy, Carmel, ed. Saint Ephrem’s Commentary on Tatian’s Diatessaron: An English Translation of Chester Beatty Syriac MS 709 with Introduction and Notes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Swanson, Reuben, ed. New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Luke. William Carey International University Press, 2005.

Swanson, Reuben, ed. New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Mark. William Carey International University Press, 2005.

Swanson, Reuben, ed. New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Matthew. William Carey International University Press, 2005.

Tatian. The Diatessaron of Tatian. Translated by Samuel Hemphill. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1888.

Secondary Sources:

Articles:

Abakuks, Andris. “A Modification of Honore’s Triple-Link Model in the Synoptic Problem.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 170, no. 3 (2007): 841–850.

Abakuks, Andris. “A Statistical Study of the Triple-Link Model in the Synoptic Problem.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 169, no. 1 (2006): 49–60.

Abakuks, Andris. “The synoptic problem and statistics.” Significance 3, no. 4 (2006): 153–157.

Abakuks, Andris. “The synoptic problem: on Matthew’s and Luke’s use of Mark.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 175, no. 4 (Oct 2012): 959–975.

Bailey, Jon Nelson. “Looking for Luke’s Fingerprints: Identifying Evidence of Redaction Activity in ‘The Healing of the Paralytic’ (Luke 5:17-26).” ResQ 48, no. 3 (2006): 143–156.

Borgen, Peder. “Miracles of Healing in the New Testament: Some Observations.” ST 35, no. 2 (1981): 91–106.

Cameron, Ron. “The Sayings Gospel Q and the Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Response to John S. Kloppenborg.” HTR 89, no. 4 (1996): 351–354.

Carlson, Stephen C. “Clement of Alexandria on the ‘Order’ of the Gospels.” NTS 47, no. 1 (Jan 2001): 118–125.

Carlston, Charles E. and Dennis Norlin. “Once More: Statistics and Q.” HTR 64, no. 1 (Jan 1971): 59–78.

Carlston, Charles E. and Dennis Norlin. “Statistics and Q: Some Further Observations.” NovT 41, no. 2 (April 1999): 108–123.

Emmrich, Martin. “The Lucan Account of the Beelzebul Controversy.” WTJ 62 (2000): 267–279.

Foster, Paul. “Is It Possible to Dispense with Q?” NovT 45, no. 4 (Oct 2003): 313–337.

Goodacre, Mark. “Fatigue in the Synoptics.” NTS 44 (1998): 45–58.

Goulder, Michael D. “Is Q a Juggernaut?” JBL 115, no. 4 (1996): 667–681.

Goulder, Michael. “Two Significant Minor Agreements (Mat. 4:13 Par.: Mat. 26:67–68 Par.).” NovT 45, no. 4 (Oct 2003): 365–373.

Hobbs, Edward C. “A Quarter-Century Without ‘Q.’” Perkins School of Theology Journal 33, no. 4 (1980): 10–19.

Honoré, A. M. “A Statistical Study of the Synoptic Problem.” NovT 10, no. 2/3 (Apr–Jul 1968): 95–147.

Kloppenborg, John S. “On Dispensing with Q?: Goodacre on the Relation of Luke to Matthew.” NTS 49 (2003): 210–236.

Kloppenborg, John S. “The Sayings Gospel Q and the Quest of the Historical Jesus.” HTR 89, no. 4 (1996): 307–344.

Koester, Helmut. “The Sayings Gospel Q and the Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Response to John S. Kloppenborg.” HTR 89, no. 4 (1996): 345–349.

Mattila, Sharon L. “A Problem Still Clouded: Yet Again: Statistics and ‘Q.’” NovT 36, no. 4 (Oct 1994): 313–329.

Mattila, Sharon Lea. “Negotiating the Clouds Around Statistics and ‘Q’: A Rejoinder and Independent Analysis.” NovT 46, no. 2 (2004): 105–131.

Mead, Richard T. “The Healing of the Paralytic – A Unit?” JBL 80, no. 4 (1961): 348–354.

Mealand, David L. “Is there Stylometric Evidence for Q?” NTS 57 (2011): 483–507.

O’Rourke, John J. “Some Observations on the Synoptic Problem and the Use of Statistical Procedures.” NovT 16, no. 4 (Oct 1974): 272–277.

Poirier, John C. “Memory, Written Sources, and the Synoptic Problem: A Response to Robert K. McIver and Marie Carroll.” JBL 123, no. 2 (2004): 315–322.

Poirier, John C. “Statistical Studies of the Verbal Agreements and their Impact on the Synoptic Problem.” CBR 7, no. 1 (2008): 68–123.

Poirier, John C. “The Synoptic Problem and the Field of New Testament Introduction.” JSNT 32, no. 2 (2009): 179–190.

Porter, Stanley E. “The Synoptic Problem: The State of the Question.” JGRChJ 12 (2016): 73–98.

Salgaro, Massimo. “The Digital Humanities as a Toolkit for Literary Theory: Three Case Studies of the Operationalization of the Concepts of ‘Late Style,’ ‘Authorship Attribution,’ and ‘Literary Movement.’” Iperstoria–Testi Letterature Linguaggi 12 (Fall/Winter 2018): 50–60.

Tripp, Jeffrey M. “Measuring Arguments from Order for Q: Regression Analysis and a New Metric for Assessing Dependence.” Neot 47, no. 1 (2013): 123–148.

Chapters and Sections:

Damm, Alex. “Ancient Rhetoric and the Synoptic Problem.” In New Studies in the Synoptic Problem: Oxford Conference, April 2008: Essays in Honour of Christopher M. Tuckett, edited by P. Foster, A. Gregory, J. S. Kloppenborg, and J. Verheyden, 483–508. BETL 239. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2011.

Farrer, A. M. “On Dispensing with Q.” In Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Edited by D. E. Nineham, 55–86. Oxford: Blackwell, 1955.

Goodacre, Mark. “Re-Walking the “Way of the Lord”: Luke’s Use of Mark and His Reaction to Matthew.” In Luke’s Literary Creativity. Edited by Mogens Müller and Jesper Tang Nielsen, 26–43. LNTS 550. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

Kahl, Werner. “Inclusive and Exclusive Agreements – Towards a Neutral Comparison of the Synoptic Gospels, or: Minor Agreements as Misleading Category.” In Luke’s Literary Creativity, edited by Mogens Müller and Jesper Tang Nielsen, 44–78. LNTS 550. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

Kloppenborg, John S. “Conceptual Stakes in the Synoptic Problem.” In Gospel Interpretation and the Q-hypothesis edited by Mogens Müller and Heike Omerzu, 13–42. LNTS 573. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2018.

Porter, Stanley E. and Andrew W. Pitts. “The Pre-Citation Fallacy in New Testament Scholarship and Sanders’s Tendencies of the Synoptic Tradition.” In Christian Origins and the Establishment of the Early Jesus Movement, 89–107. TENTS; Brill, 2018.

Reid, Barbara E. “‘Do You See This Woman? A Liberative Look at Luke 7.36-50 and Strategies for Reading Other Lukan Stories Against the Grain.” In A Feminist Companion to Luke, edited by Amy-Jill Levine, 106–120. London: Sheffield, 2002.

Watson, Francis. “Luke Rewriting and Rewritten.” In Luke’s Literary Creativity, edited by Mogens Müller and Jesper Tang Nielsen, 79–95. LNTS 550. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

Books and Dissertations:

Abakuks, Andris. The Synoptic Problem and Statistics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2015.

Abbott, Edwin A. The Corrections of Mark: Adopted by Matthew and Luke. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1901.

Agresti, Alan and Barbara Finlay. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009.

BeDuhn, Jason David. The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Salem, OR: Polebridge Press, 2013.

Butler, Basil Christopher. The Originality of St. Matthew: A Critique of the Two-document Hypothesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

Chapman, John and John M. T. Barton. Matthew, Mark and Luke: A Study in the Order and Interrelation of the Synoptic Gospels. London: Longmans, Green, 1937.

Damm, Alex. Ancient Rhetoric and the Synoptic Problem: Clarifying Markan Priority. BETL 252. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2013.

Derico, T. M. Oral Tradition and Synoptic Verbal Agreement: Evaluating the Empirical Evidence for Literary Dependence. Eugene: Wipf&Stock, 2016.

Dungan, David L. A History of the Synoptic Problem: The Canon, the Text, the Composition and the Interpretation of the Gospels. New York: Doubleday, 1999.

Ennulat, Andreas. Die “Minor agreements”: Untersuchungen zu einer offenen Frage des synoptischen Problems. WUNT 2/62. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1994.